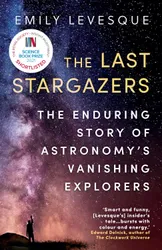

I’ve read books about astronomy before, such as the excellent Our Universe, and these have touched on the methods used by astronomers to learn about the universe around us. But this book takes an astronomer’s eye view of the field, showing us what it’s like to be an astronomer working with telescopes, collecting images and data, and figuring out new things about how the universe works and what’s out there.

One of the problems with observing space from Earth is that the atmosphere affects our ability to see clearly. So we build telescopes in places to try and minimise these problems, such as high up mountains, on aeroplanes, or in space. We also use telescopes that look at other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum instead of visible light. Several different types of telescopes are featured in the book, including optical, radio telescopes, telescopes in aeroplanes, and space telescopes such as the famous Hubble Space Telescope. All of these are used for different purposes, and have different ways of operating, and the book gives a really good sense of how these differ from the point of view of the astronomers using them. The author herself has worked at observatories to collect data for her own research on red supergiant stars, and also used other types of telescope, including getting airborne in one of the flying telescopes.

In working with, and interviewing, other astronomers, and through her own experiences, Levesque has a great collection of observing anecdotes about the things that can go wrong when working at telescope. Some of these are amusing, but in one case things end tragically. The book conveys the challenges of working with such large and delicate pieces of equipment, and the strangeness of being awake when everyone else is asleep.

Why are these “Astronomy’s Vanishing Explorers” as the subtitle suggests? Towards the end of the book, Levesque discusses the telescopes that we’re building now, such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile. Increasingly, these are automated facilities that survey the night sky systematically and make their data available to all astronomers. While this means much more astronomical data being collected, it reduces the need for observers to visit telescopes themselves, and also reduces the opportunity for spontaneous adjustments to targets and observing plans. So the breed of astronomer depicted in this book may become much rarer, or disappear altogether. However, Levesque makes the case that we’ll always need to do the more ad-hoc types of observing in order to investigate interesting things that the automated telescopes have picked up.

I loved reading this book! I found the descriptions of life at an observatory really fascinating, and I really enjoyed all the anecdotes and personal stories that Levesque shared from her observing experiences. She weaves scientific knowledge throughout the book in subtle ways without it ever feeling like she is teaching you, and the book’s perspective from the point of view of working astronomers visiting telescopes is unique among the books I’ve read so far. If you have any interest in astronomy, I really recommend this book.